Seasonal Forecast: A Wetter-Than-Normal Summer for the East; Heat and Wind in the West

Vox Weather Meteorologist Annette Botha gives us the details on the 2025 / 2026 summer season – looking back on some of the drama that the weather has recently thrown at us, and what we can expect going into next year.

You can also click here to see Annette presenting this information in a short video in Afrikaans, as part of the regular ‘Langtermyn Landbou-Weervoorspelling’ series, and experience some spectacular additional video footage of recent weather-related visuals that are highlighted here.

South Africans have just come through one of the most dramatic Novembers in recent years – it was a month marked by relentless thunderstorms in the north and east, with widespread hail, local flooding, and strong winds in the Western Cape.

Now, as we turn the corner into December, the latest seasonal forecasts point to a summer of strong contrasts: wet, stormy and cooler in the east, but hot, windy and fire-prone in the west.

A Record-Breaking End to Spring

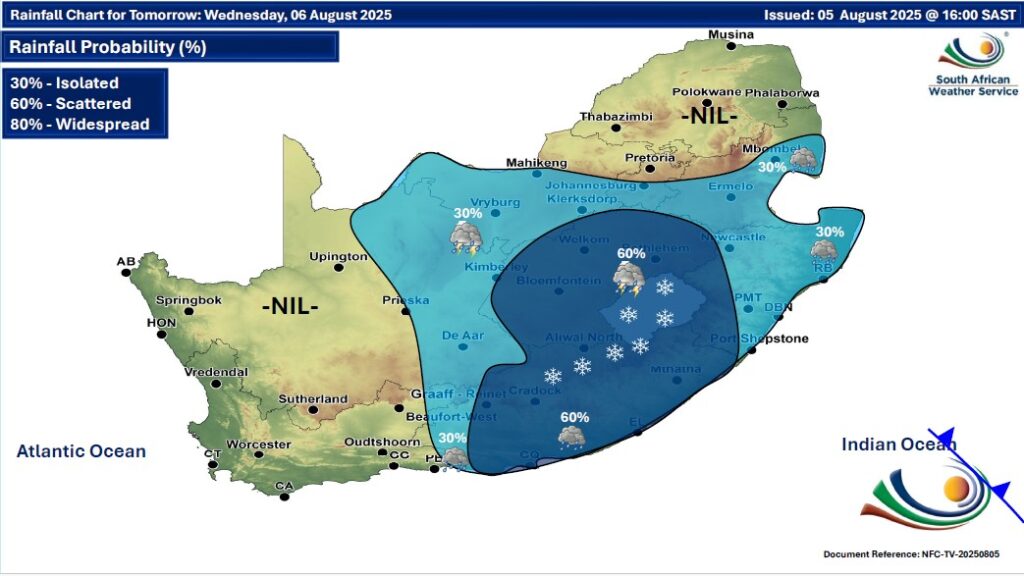

November delivered an onslaught of thunderstorms across Gauteng, Limpopo, North West, the Free State and the drought-stricken Eastern Cape. Many large dams responded quickly: the Vaal, Gariep and Bloemhof Dams rose sharply, with several spilling over.

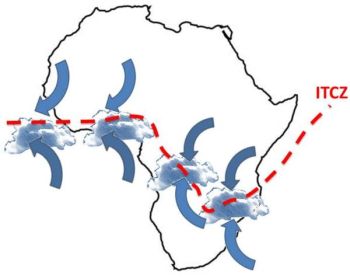

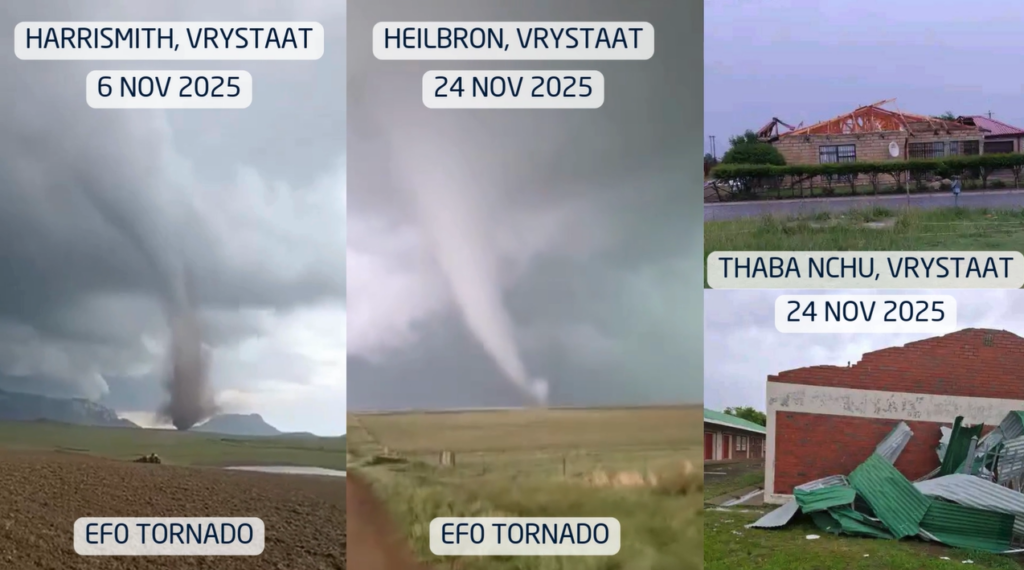

Thunderstorms were fuelled by unstable, moisture-rich tropical air that repeatedly surged across the interior. More than one EF0 tornado was reported in parts of the Free State, a reminder that South Africa’s ‘tornado corridor’ can produce short-lived but destructive events almost every summer.

Hail was another standout feature of the month. In some towns, small hail accumulated so thickly that streets resembled winter scenes, trapping cars and residents. In other areas, hail the size of chicken eggs caused extensive damage to vehicles, roofs, gardens and crops. Farmers across the Free State and neighbouring regions faced the difficult balance of ‘good rain, but big losses’.

Meanwhile, in dramatic contrast, the Western Cape battled powerful southeasterly winds, fanning multiple wildfires across the Cape metro and agricultural zones. Homes were evacuated and producers faced early-season challenges with wind damage, low soil moisture, and fire risk.

How Much Rain Actually Fell?

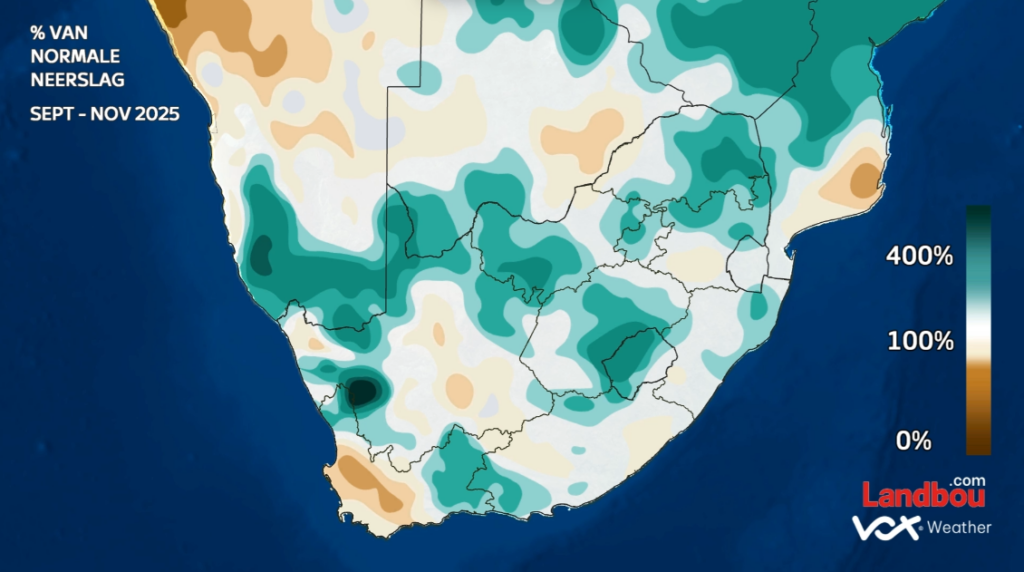

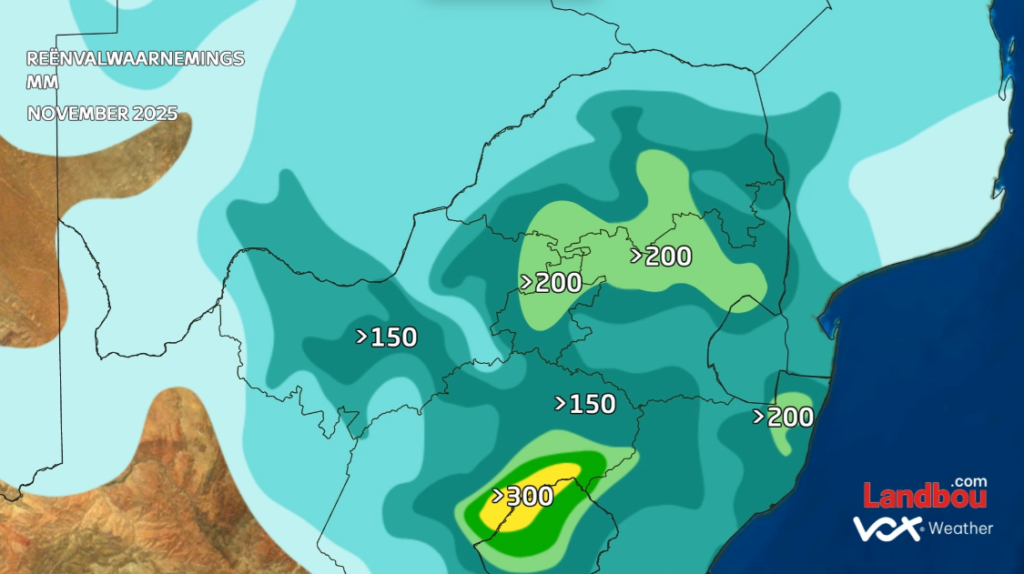

November did not just feel wet, it was exceptional. Large areas of the summer rainfall region recorded more than 150mm for the month, with pockets exceeding 200mm. To put this into perspective: Pretoria’s long-term November average is around 90 mm. Many regions received more than double their normal rainfall.

While the interior soaked, the Karoo, Eastern Cape and Western Cape experienced a notably drier spring, aligned with the persistent windier pattern that dominated the southwest.

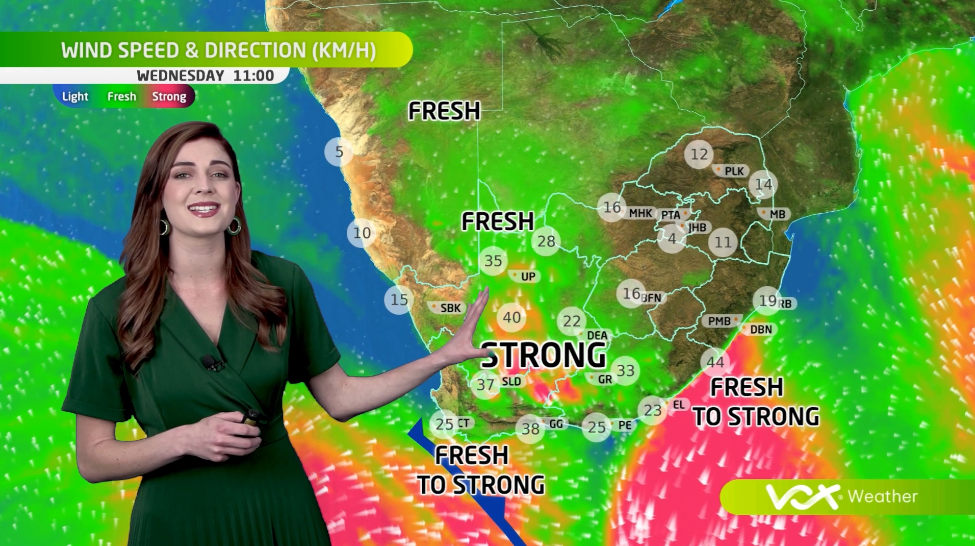

December Wind Outlook: More Gusts on the Way

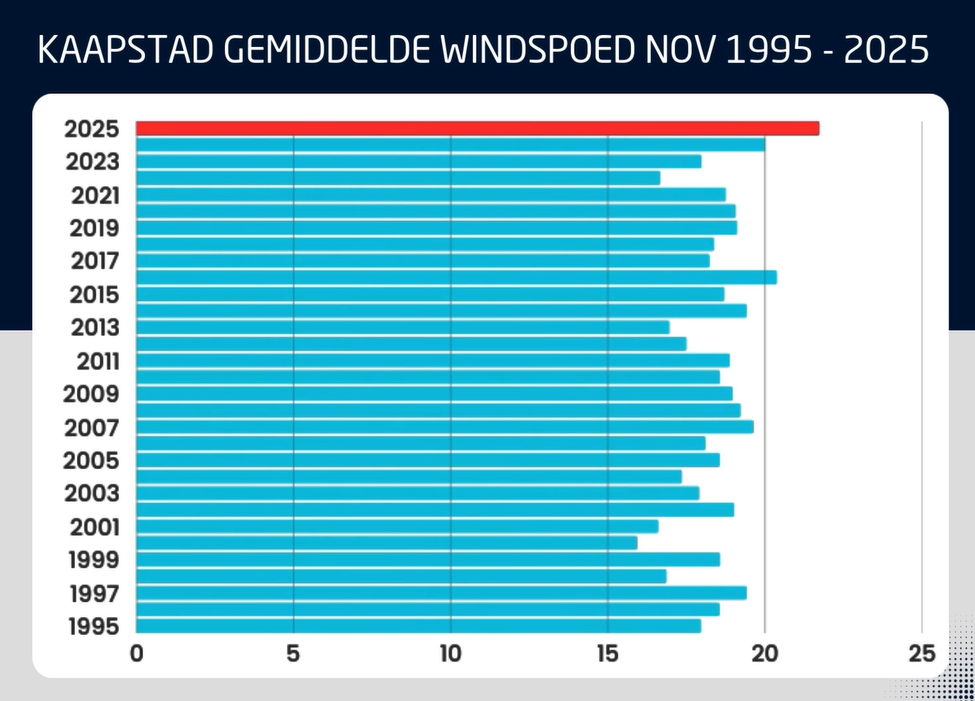

November 2025 was confirmed as the windiest November since 1995 over the Western Cape based on 30-year wind-speed averages.

Unfortunately for Capetonians, the models show continued above-normal windiness in December.

This raises wildfire danger even further heading into the heart of the festive season.

Dams, Climate Drivers and What is Shaping the Season

Dam levels remain high across the interior and are expected to climb further with continued rainfall. In contrast, dams in the Western and Southern Cape are dropping quickly, with some municipalities already preparing for potential water restrictions.

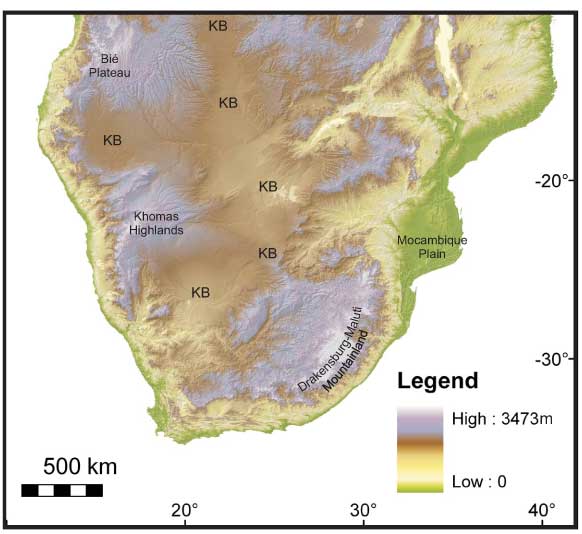

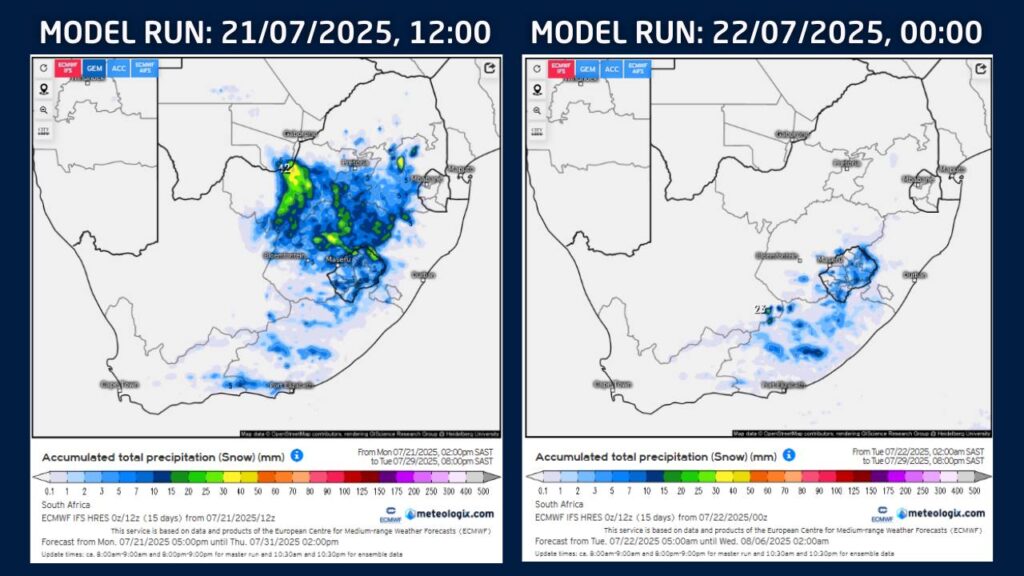

Globally, the climate system is reinforcing the wet-summer signal. We remain in La Niña conditions, and the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is in a negative phase, a combination that historically supports above-normal summer rainfall for South Africa’s summer rainfall belt.

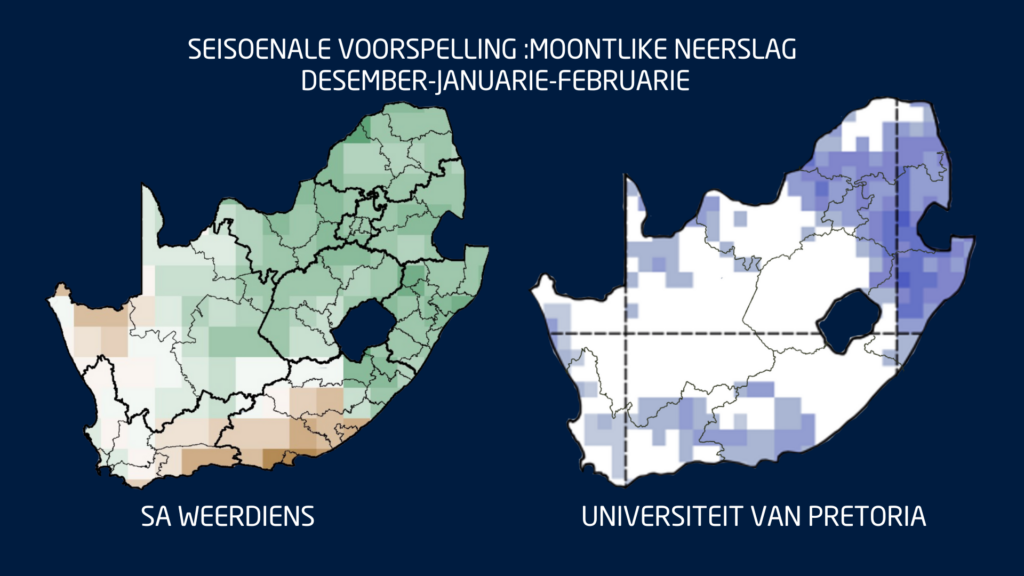

This means that December through February (DJF) still shows strong model agreement: a wetter-than-normal summer across the central and eastern parts of South Africa.

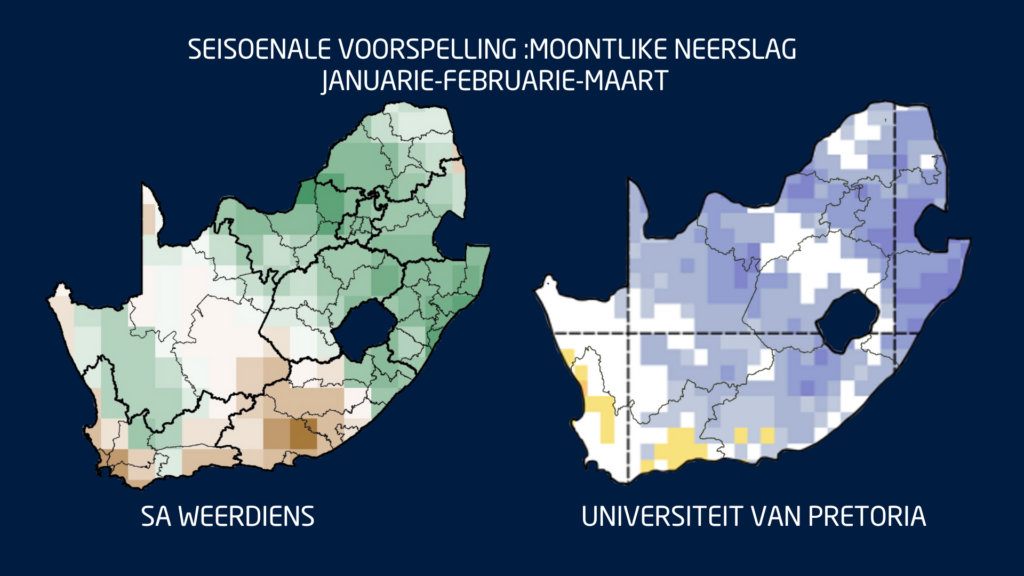

The only region where uncertainty remains is the Eastern Cape, ironically one of the provinces most in need of sustained rain. Seasonal guidance for January to March (JFM) keeps the same pattern: above-normal rainfall inland, with drier-than-normal tendencies persisting over parts of the Southern Cape.

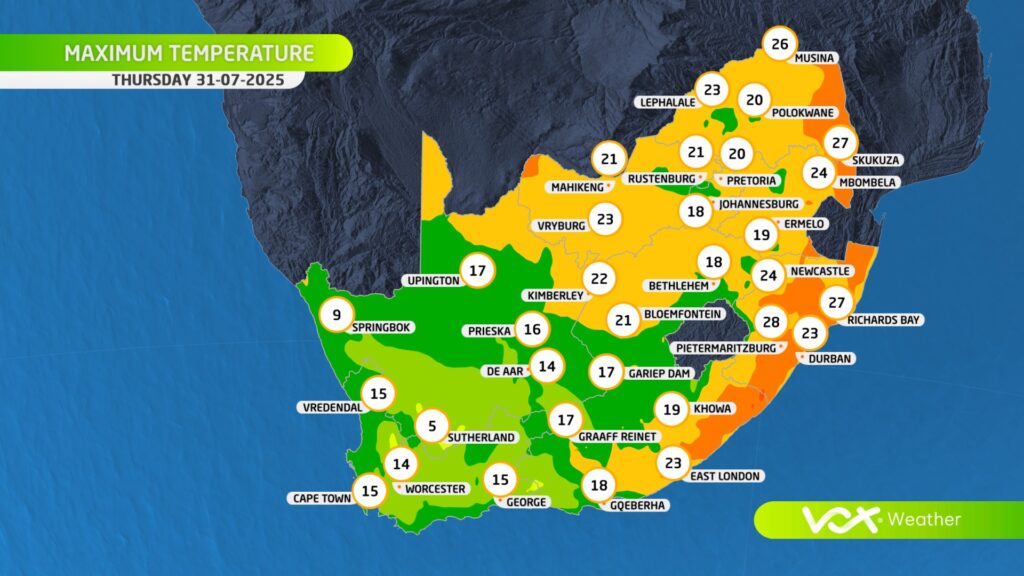

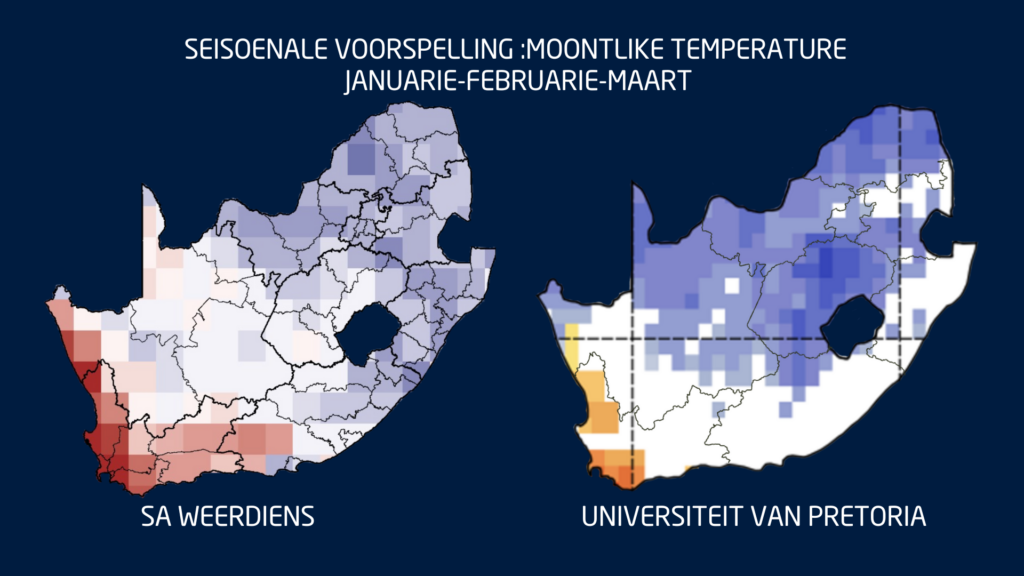

Temperatures: Cool in the East, Very Hot in the West

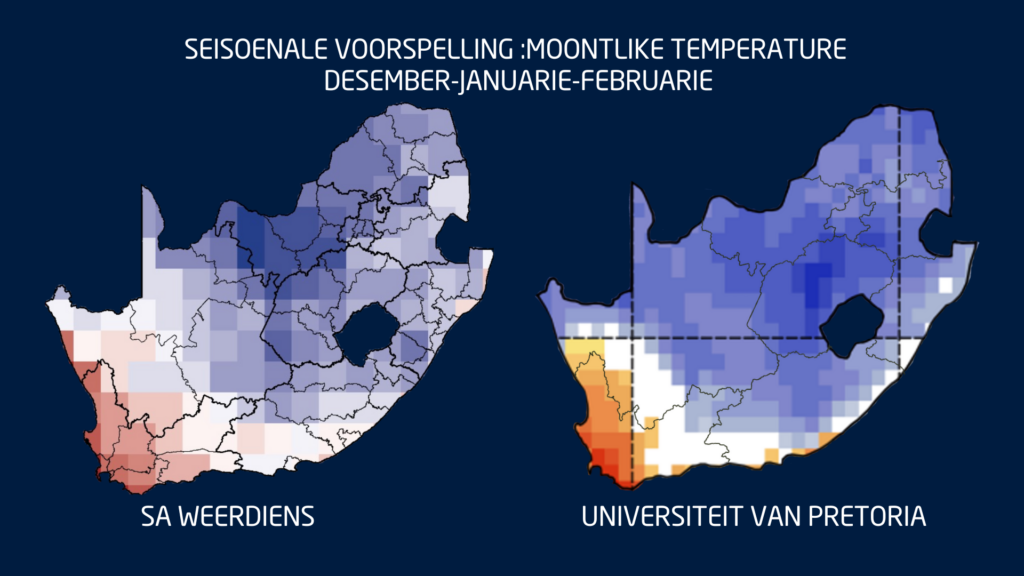

Where rainfall increases, maximum temperatures are expected to trend lower. Much of the summer rainfall region may see cooler-than-normal daytime temperatures through summer and early autumn.

However, the Western Cape, Northern Cape and Namakwa can expect very hot, windy conditions, especially toward the end of summer and into early autumn, a period when fire danger typically peaks.

What to Expect Week to Week

Short-term and sub seasonal models show a continued pattern of:

- Repeated thunderstorm activity over the central and eastern interior;

- Occasional heavy rain and local flooding;

- Persistently gusty southeasterly winds in the southwest; and

- Episodic heatwaves in the western interior

Farmers, disaster managers and residents should prepare for a summer with sharp contrasts: regular storms and good rain inland, and ongoing heat and fire risk in the west.

And finally a quick note to close off the year:

The Vox Weather ladies will be on annual leave for the festive season, but Vox Weather followers will still receive the daily weather maps throughout the period.

And so from Annette and Michelle: Wishing you a wonderful holiday period – travel safely and know that Vox Weather is always here to help you with your planning and continue ‘putting the WE back into Weather’!