Vox Weather Viewer Numbers Continue to Climb Across Multiple Technology Platforms

Vox Weather puts the ‘we’ back into weather, assisting both individuals and businesses

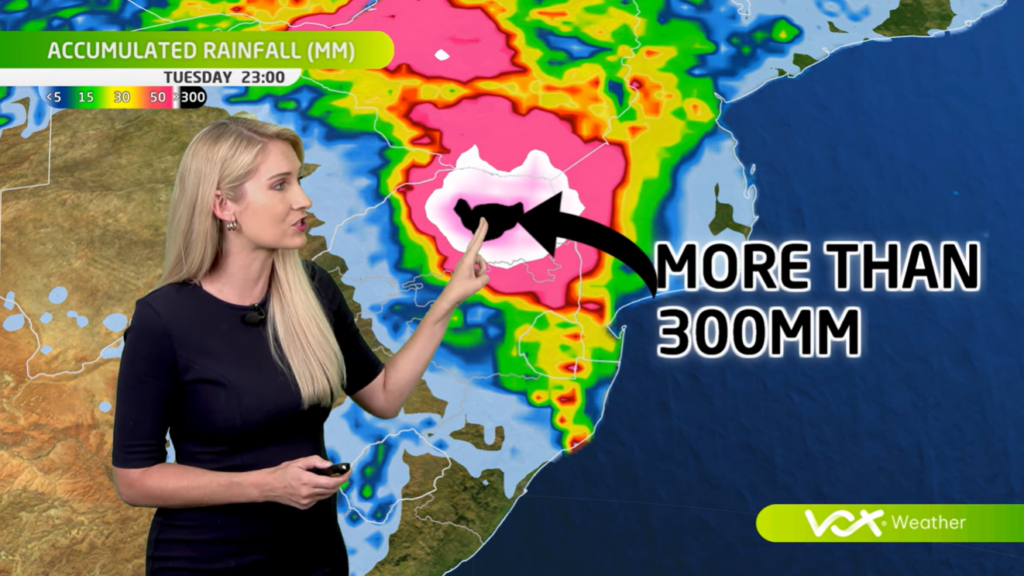

As South Africa grappled recently with the extreme weather across the country this summer, its citizens were more invested than ever in following daily weather forecasts. Local viewers – and even some in neighbouring SADC countries – have been following the solid expertise and skilled presentation of Vox Weather’s popular Meteorologists, Annette Botha and Michelle du Plessis, in rapidly increasing numbers. Vox Weather is conveniently presented on multiple platforms including its home web page as well as Facebook, YouTube, X, Instagram, WhatsApp, TikTok and LinkedIn.

Vox Weather was launched and managed by telecommunications and IT services provider Vox some four and a half years ago, in late 2021. Its rapidly climbing follower numbers are a testimony to this daily presenter-led weather update, which provides facts and scientific forecasting with warmth and style.

We take a closer look at how Vox Weather has become another successful subsidiary of Vox, and the important role that personal weather forecasts play in citizens’ lives, as well as facilitating strong businesses and regional economies.

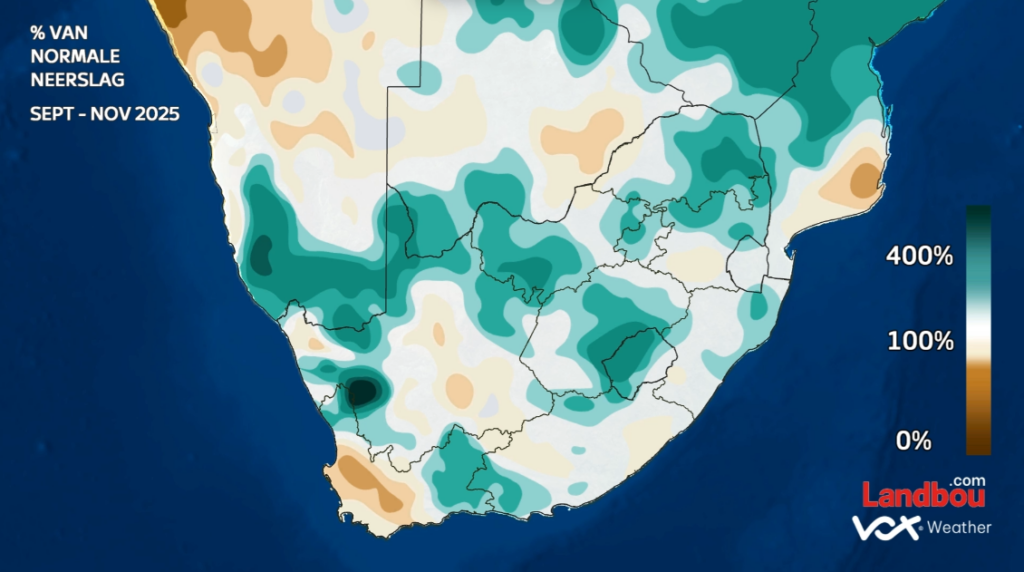

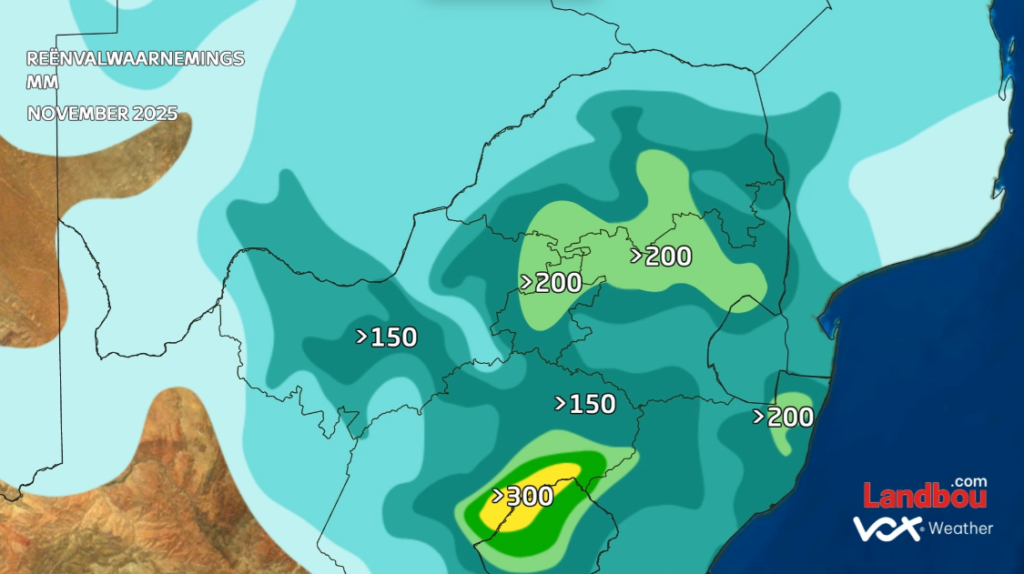

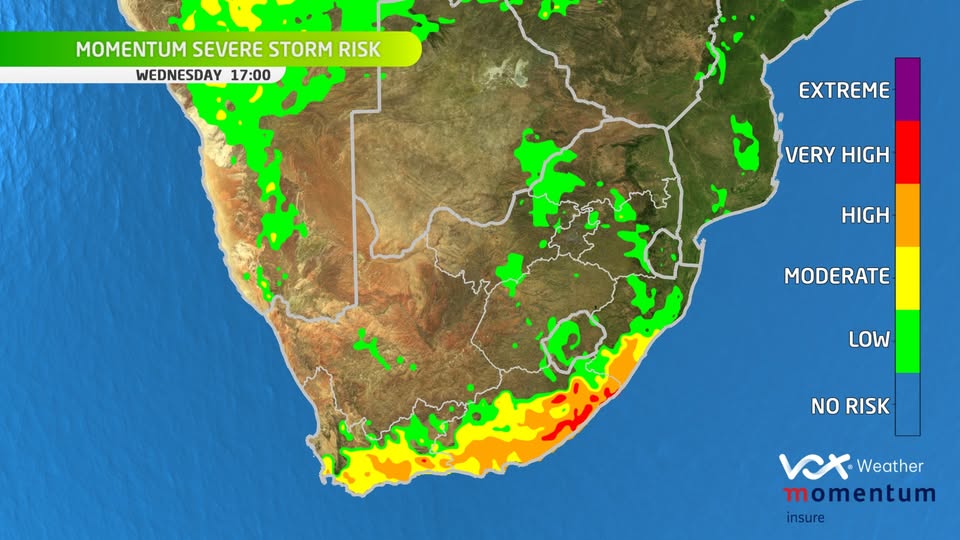

Vox Weather also offers a partnership with agricultural media Landbou.com, providing important weather information to its readers in the agricultural sector, as well as Momentum Insure within the insurance arena. Vox Weather developed a Severe Storm Risk Map specifically for its collaboration with Momentum Insure, which aligns well with the severe storm season South Africa is currently experiencing.

Vox Weather: ‘We are Go for Growth’

Vox Weather achieved its first significant milestone when it grew to 50,000 followers within its first six months of launching. After this, the platform took just another year to double up to 100,000 dedicated followers, with a reach of close to two million people per month, on average, in its first 18 months. Last year, Vox Weather crossed the half-a-million viewers mark – truly impressive!

Vox believes that there are multiple reasons for this pleasing growth. Its presenters are both highly qualified scientists, bringing enormous credibility to their weather presentations, and preparing the visuals themselves from the raw data. In addition, they are personable and friendly, with a truly empathetic understanding of how important the weather is in people’s daily lives.

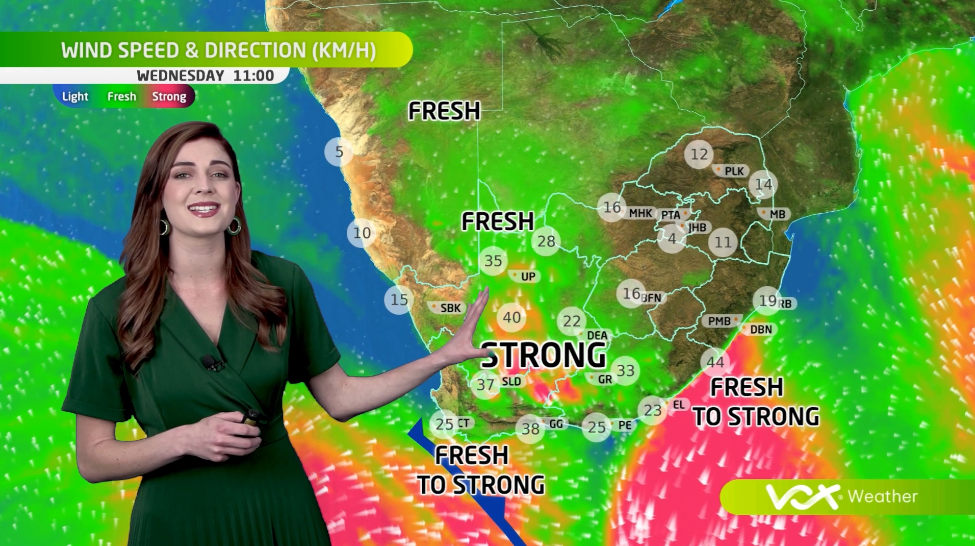

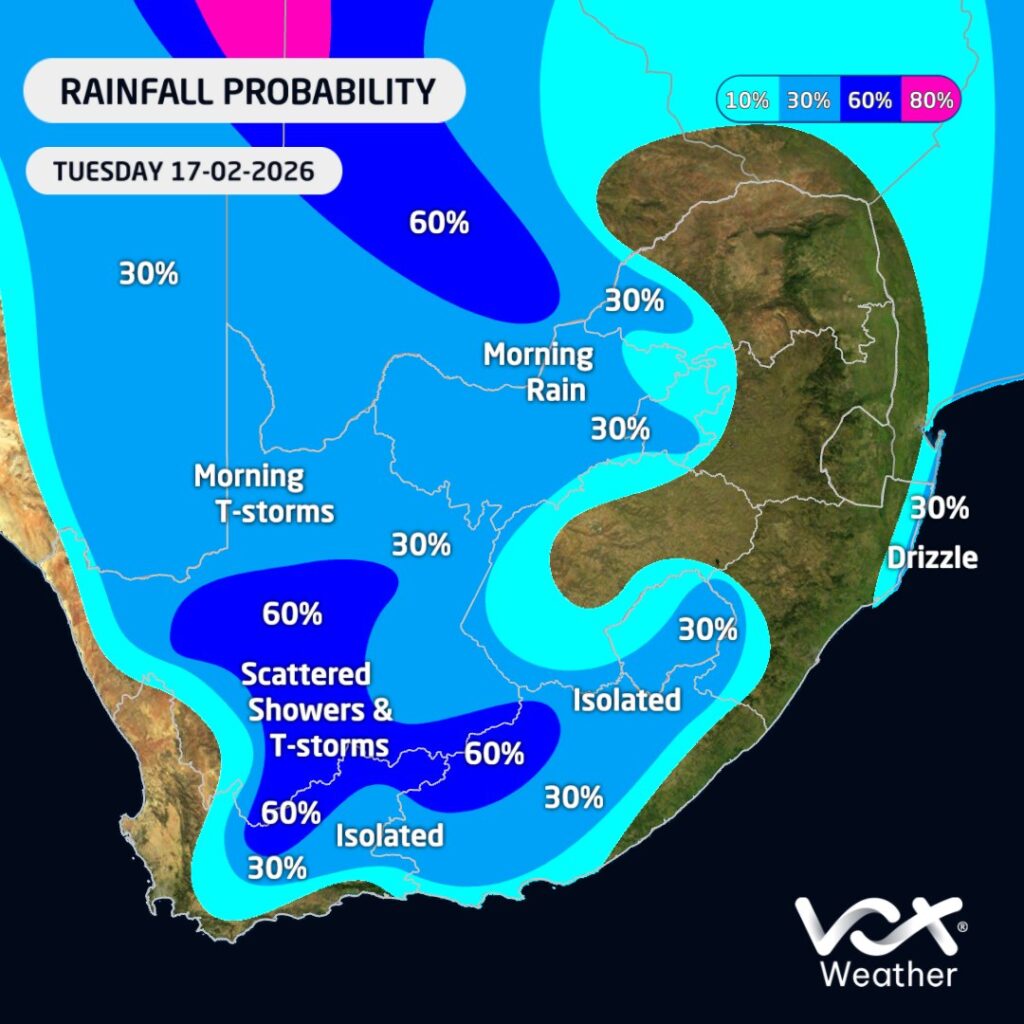

The animated graphics are professional, modern, visually pleasing and easy to understand. Finally, Vox Weather makes excellent use of multiple social media platforms to actively market its content.

Vox Weather’s social media numbers have recently achieved some additional milestones.

Vox Weather started 2026 on a strong note, with a reach of 7.3 million and 12.9 million views. Having previously reached 500,000, as outlined, Vox Weather’s audience is now sitting at 594 647, gaining 15 300 followers in January. A behaviour measurement tool on WhatsApp shows that audiences are sharing the content more than simply reacting to it, which is an additional win.

It couldn’t be easier to access Vox Weather reports via the platform of your choice, whether you are in the office with your laptop, or on the go and looking at your mobile phone. This has been particularly useful for viewers this past summer as multiple weather events and patterns across the country continued to surprise the country with their intensity.

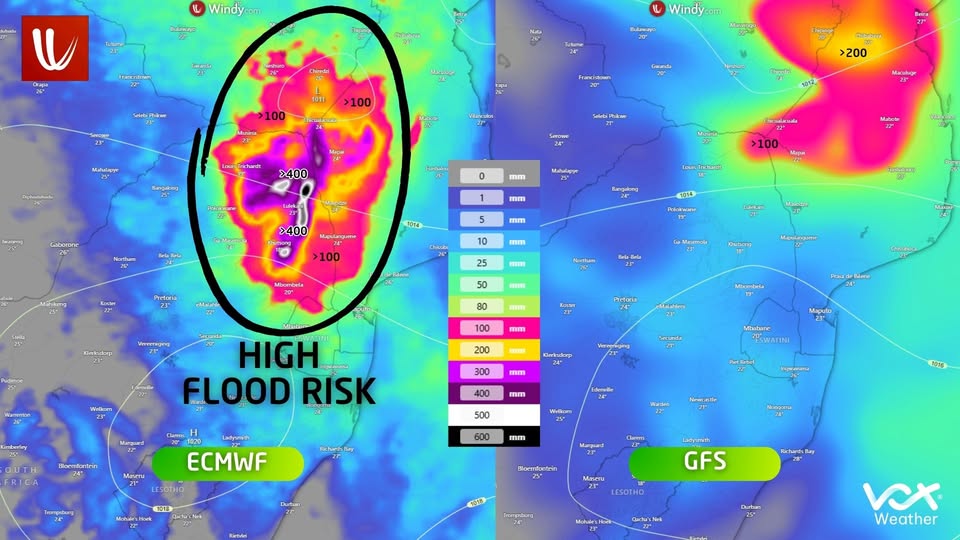

Vox is very pleased that the forecasts brought by Vox Weather are able to assist people and their personal safety, at the individual level, by giving them the knowledge to potentially avoid dangerous situations involving hailstones, high UV indexes, flooded areas and high winds, to name but a few.

The Importance of Weather Commentary

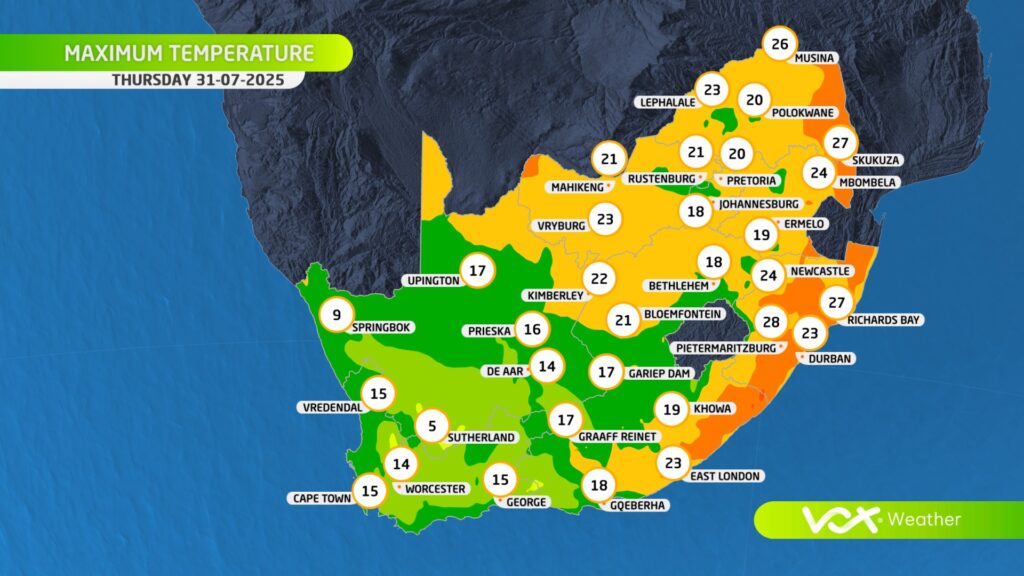

Locally, every province in South Africa has recently had its own collection of stories to tell about recent weather patterns. Vox Weather’s Meteorologists were ever ready to unpack the facts, present forecasts and communicate warnings when the weather was heading once more into extreme territory.

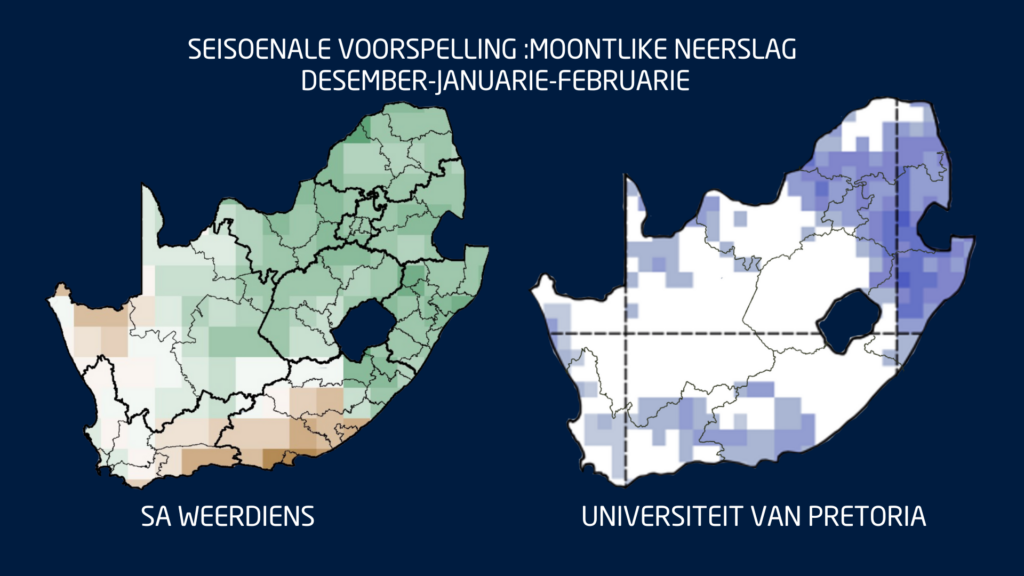

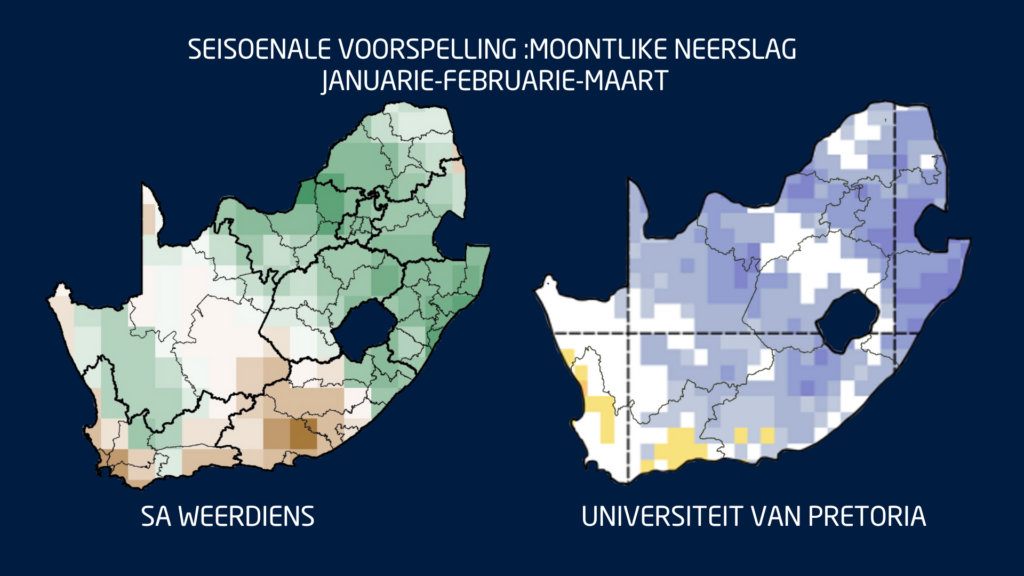

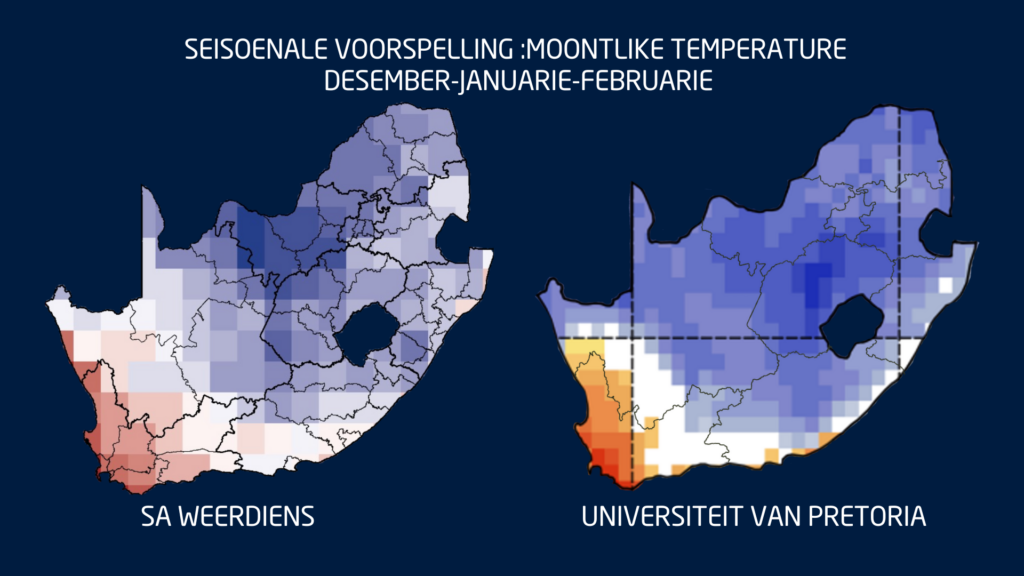

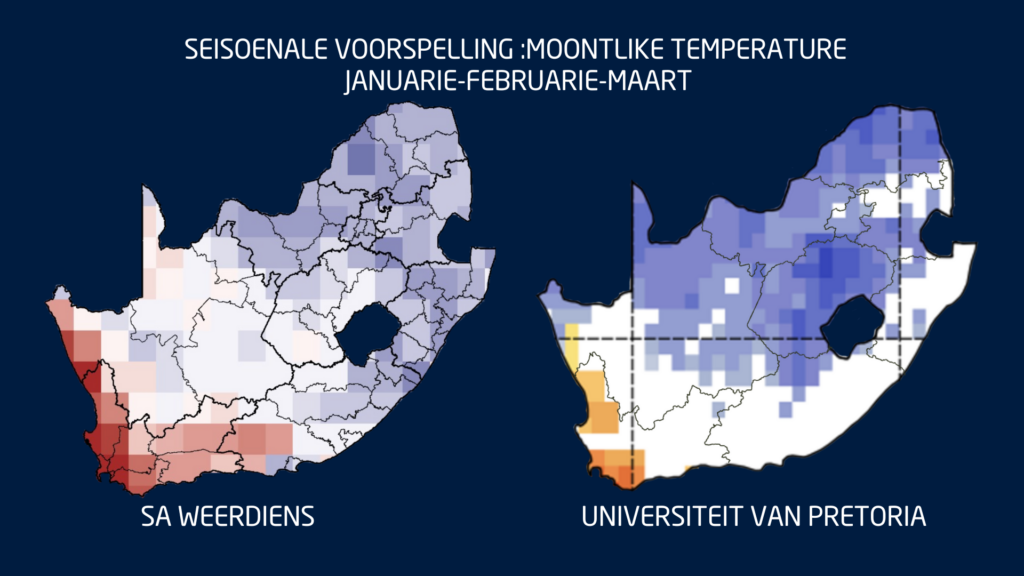

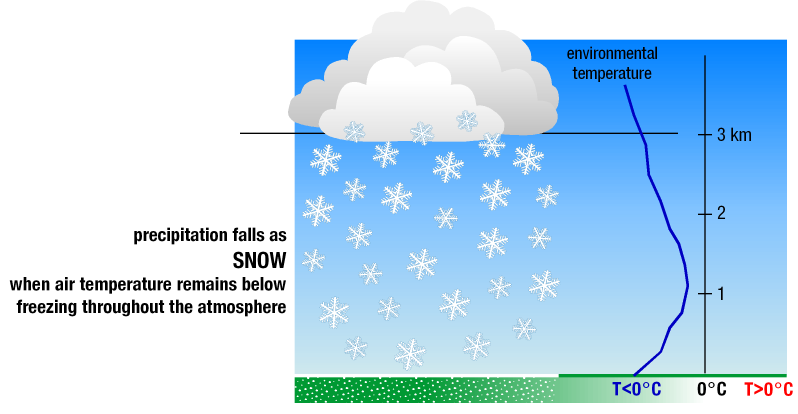

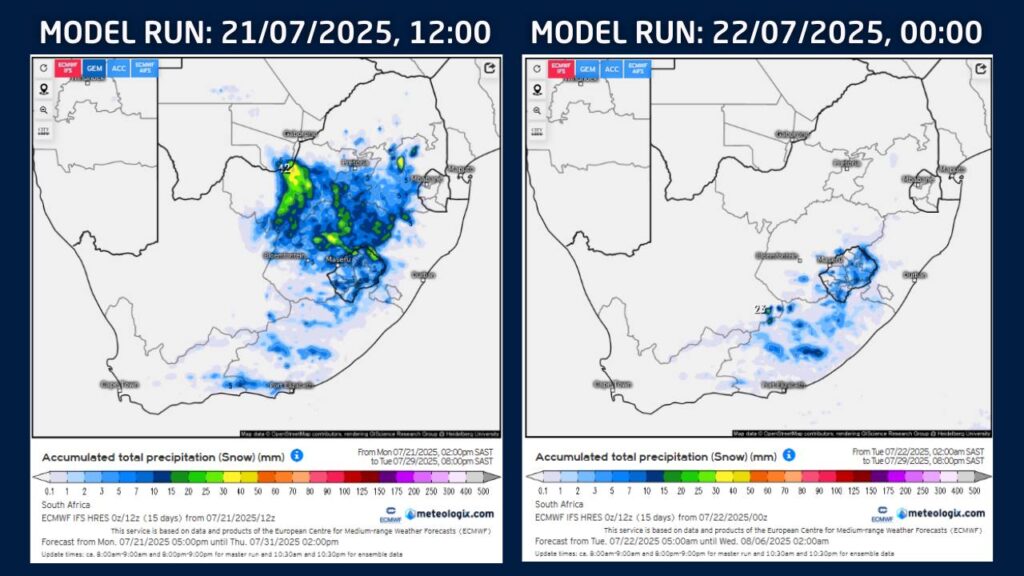

Annette explains: “Weather forecasting models are designed to predict various weather phenomena such as sunshine, rain, snow, wind and severe storms like thunderstorms and hurricanes. Different models and data are used for different planning needs, including forecasts for aviation, marine activities and fire hazards.”

She notes that prediction timeframes include short-range (hours to days); medium-range (three to seven days); and long-range forecasts (eight to 14 days predictions), and that longer seasonal forecasts also have an important role to play in the planning aspects of certain industries.

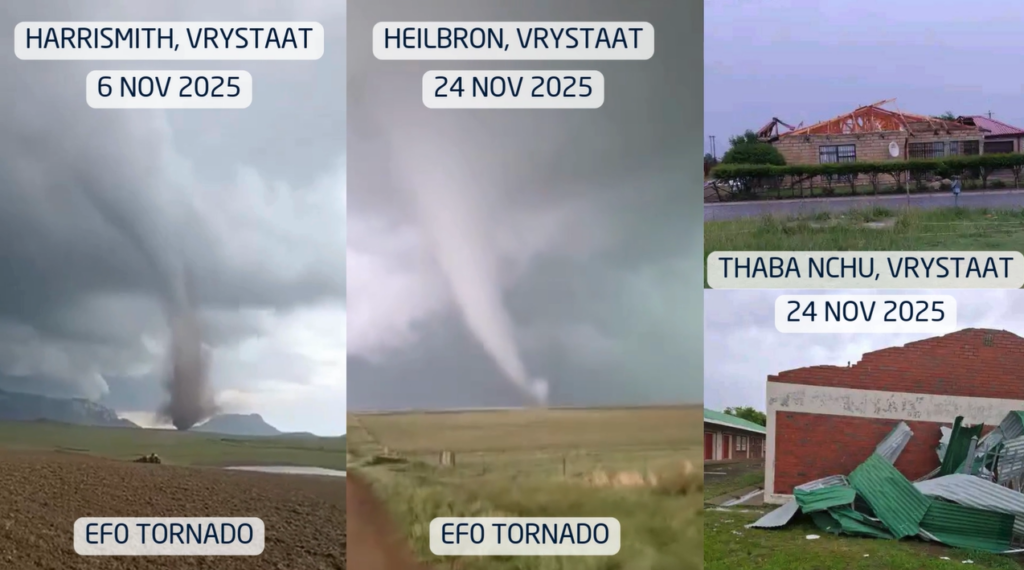

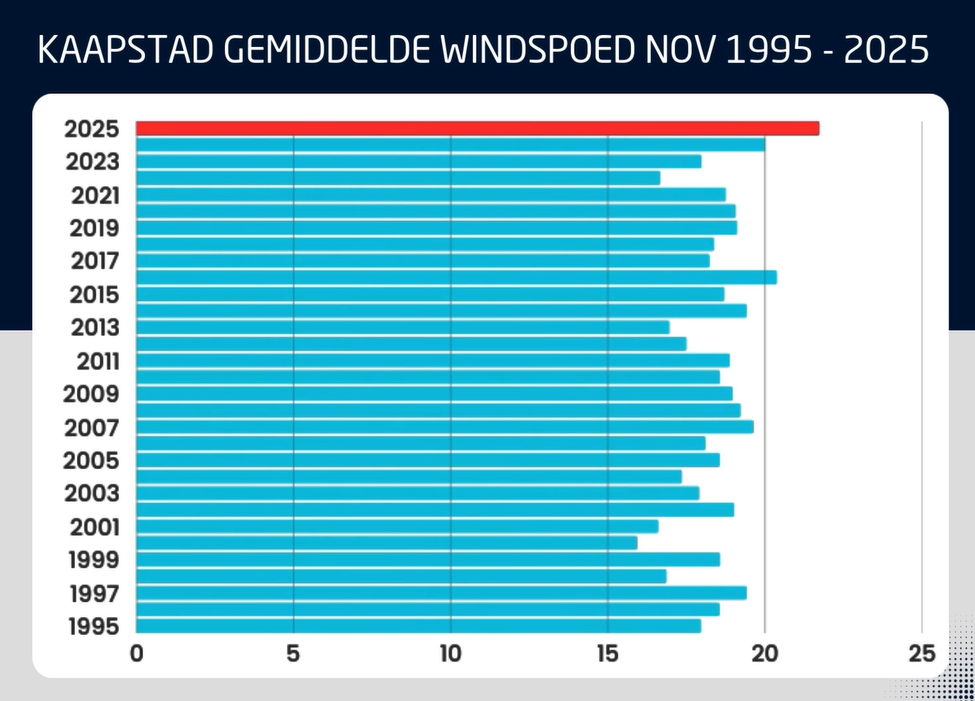

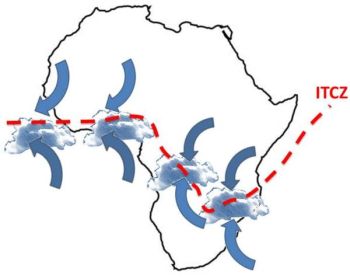

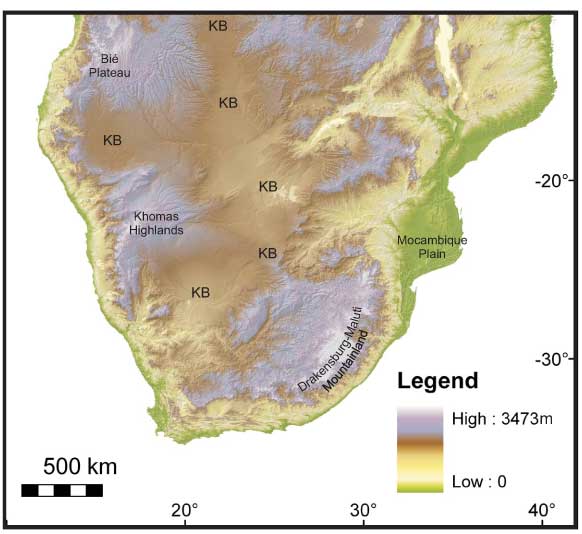

Annette continues: “We have seen residents in parts of the Eastern Cape battling with the looming threat of a lack of water supply due to drought conditions, while the Free State experienced massive hailstorms and even tornadoes. In contrast, the Western Cape battled extreme dryness and wildfires, and in the north, residents of Mpumalanga and Limpopo braved deadly floods, including in the Kruger National Park.”

Michelle adds: “When we think about the recent floods in the Kruger National Park, we know that rivers don’t rise slowly. Rain that falls hundreds of kilometres away can rush downstream, filling river channels in hours. That’s why flood warnings matter, and why you should never underestimate moving water. Nature is beautiful – but it’s also incredibly strong, as we have seen all summer long!

“All these wide-ranging weather-related issues have had a potential impact on people’s lives, with awareness of forecasts being even more important for both individuals and businesses alike during times of extreme weather events.”

Weather’s Economic Impacts

Seasonal and long-range forecasts are important for industries with high capital investment and/or long production cycles, as well as those that can be highly sensitive to climate, weather or economic trends. Key industries that rely on longer-term forecasts include agriculture, of course, as well as transportation and logistics, construction and real estate, and insurance and reinsurance, to name but a few.

Vox believes that during challenging economic times, it’s even more important for companies and industries to have an awareness of potentially threatening weather conditions that could have an impact on their operations, and here again Vox Weather is able to assist businesses as well as individuals.

Overall, Vox Weather has seen a strong start to 2026, with a healthy reach and constant engagement. As the parent company, Vox is proud to have played a role in bringing the dynamic duo of Annette and Michelle to South Africa’s social media reach across multiple technology platforms, and looks forward to its continued growth throughout the rest of the year.